Above, On, and Below the Surface: UVA Researchers Collaborate on Strategies to Address Snow and Water Dynamics in the Arctic

UVA’s Environmental Institute (EI) recently announced the third Climate Collaborative, supporting a team of researchers whose longstanding work in the Arctic brings together approaches across environmental science, engineering, architecture, planning, landscape architecture, and social sciences. The team, led by researchers at the University of Virginia’s Arctic Research Center and federal and community partners, will study and propose maintenance strategies that address the dynamics of snow and water in a region that has faced extreme environmental conditions for thousands of years. Specifically, they will focus intensively on Utqiaġvik, the northernmost urban center in Alaska, largely comprised of the Iñupiat who rely on and cultivate a subsistence economy.

Launched in 2023, EI’s Climate Collaborative program funds large, interdisciplinary research teams in specific localities dealing with climate-related challenges. A goal of the program is to support actionable strategies that are co-created by university researchers and external partners. The core Arctic team includes Howard Epstein (UVA Environmental Sciences), Leena Cho (UVA Landscape Architecture), Matthew Jull (UVA Architecture), Caitlin Wylie (UVA Engineering and Society), several postdoctoral research associates including Hannah Bradley (UVA Engineering and Society), Anna Wagner (Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory), Lars Nelson (TRIBN, Inc. and former North Slope Borough Assembly Member), and Ukpeaġvik Iñupiat Corporation members.

Building on knowledge gained through the team’s current NSF-funded research based in Utqiaġvik that includes the deployment of an integrated sensor network to leverage environmental data that can inform the management of building and infrastructure and the development of planning initiatives in the town, the $1.5 million Climate Collaborative award, which starts in January 2025 for a three-year project period, will help catalyze solutions alongside the people of Utqiaġvik by addressing one of their most pressing and enduring challenges: permafrost thaw.

Changing Dynamics of Water and Snow: The Degradation of Permafrost

Utqiaġvik is built on permafrost, ground that is perennially frozen and made up of soil, rock, water, and organic material — the top layer of which thaws and refreezes each year. In Utqiaġvik, like many other Arctic regions, rising average temperatures are increasing the depth of thaw and therefore degrading the upper layer of the permafrost. With this permafrost degradation comes a series of negative consequences from shifting or failing building foundations and coastal erosion, to destabilized transportation infrastructure and local health risks.

Additionally, due to the acceleration of the hydrological cycle and a warming atmosphere, increased precipitation and earlier snowmelt (known as "spring break-up") have led to greater pooling of surface meltwater, frequently resulting in urban flooding. These direct effects of climate change, combined with infrastructure and management practices—such as drainage systems and snow fences—alter the distribution and behavior of surface water and snow, exacerbating flooding risks.

“As a Climate Collaborative, we will be able to add members to our core team with expertise in snow and surface water hydrology to focus on how snow can be managed in ways that make infrastructure and ecosystems most resilient in Utqiaġvik,” said Epstein. While our work focuses on Utqiaġvik, the findings are highly relevant for other Arctic communities.”

In Utqiaġvik, the research team proposes to study these patterns of water and snow and their social contexts to better understand how they impact the stability of the permafrost. To do so they plan to use traditional and institutional knowledge with environmental sensing in the field, remote sensing, and hydrological and thermal modeling. Their methods will also inform design, planning, and maintenance strategies for the city, emphasizing snow and meltwater management to ensure long-term stability of the underlying permafrost.

Like a hidden glue that holds a surface together, the frozen permafrost’s stability defines how the people of Utqiaġvik make their livelihoods and their homes. "Permafrost is one of the most profound features of the socio-environmental system in the Arctic. Building supports, pipes for moving gas and liquids, ice cellars for food storage, and cemeteries all rely on the stability of the permafrost,” the team described in their proposal.

Establishing Partners in Place: Learning from and Producing with Utqiag

Several members of the UVA Arctic Research Center (Cho, Epstein, and Jull) joined forces in 2018 after years of working in the Arctic region individually, on fundamental research and through teaching. In 2020, Wylie joined them to integrate social sciences and the methodology of co-production of knowledge into the team’s research. That foundation of knowledge, experience, and relationship-building, built over time, has proven invaluable and has shaped a strong ethos of collaboration that has led to their recognized collective insights and actions over the last decade — including building datasets, design and planning guidelines, educational resources, strategies for interdisciplinary collaboration, and partnerships directly with Arctic communities.

Their partnerships in Utqiaġvik include local and borough governments, utility cooperative, Tribal organizations, Elders, teachers, youths, and more. They have established relationships with the North Slope Borough and their Departments of Public Works, Planning, and Capital Improvement Projects, the Barrow Utilities and Electrical Co-op, the Arctic Slope Native Association, Iñupiat Community of Arctic Slope, the Taġiuġmiullu Nunamiullu Housing Authority, the Boys & Girls Club of Utqiaġvik, Barrow High School, and Iḷisaġvik College, among many others.

Building on these partnerships, a key methodological component to the Climate Collaborative project will be to establish a Community Board, comprised of five community leaders based in Utqiaġvik. To understand the complex socio-ecological challenges of permafrost stability, a close collaboration with Utqiaġvik residents is necessary, both to produce reliable and comprehensive knowledge about snow and water dynamics, and to inform actionable recommendations for snow and water management policies for the town.

As the team presented in their proposal, Arctic Indigenous communities prefer and expect researchers to follow the collaboration framework of co-production of knowledge, in which community residents and academics are equal research partners who together design project questions and methods, and collaborate on analyses and interpretation of results. There has been a significant recent increase in Arctic studies that use co-production, yet researchers still disagree about what co-production means in practice.

Unique to this study, the team of researchers and Arctic residents will co-produce knowledge about snow and water dynamics and management, while also studying how and how well they are doing this. Led by Co-PI Caitlin Wylie and postdoctoral researcher Hannah Bradley (PhD in Anthropology), the team will collect ethnographic observations, interview all team members and community collaborators, and provide practical feedback about community-academic interactions in a co-productive project. Their insights will help to inform best practices for ethical collaboration with communities.

Wylie explained, “Only by bringing together expertise from Indigenous knowledges, Arctic residents’ lived experiences, and a variety of academic disciplines can we understand climate change, climate resilience, and climate adaptation. But in practice, integrating different kinds of knowledge is really hard. Our role as social scientists is to study how our team collaborates, to provide real-time feedback as well as general guidelines for ethical, equitable co-production of knowledge across disciplines and between researchers and communities.”

Planning, Design and Social Frameworks for Protecting Permafrost

Over the course of the multi-year Climate Collaborative, the team will engage in multiple methodologies including field observations, oral history, social network analysis, remote sensing, and hydrological modeling. Wylie and Bradley plan to incorporate social dimensions into the broader analysis of snow and water management systems. Wylie described, “We will study the history of planning and water management in Utqiagvik, to better understand the cultural context and inform how the team and our local partners think about possible future policies.”

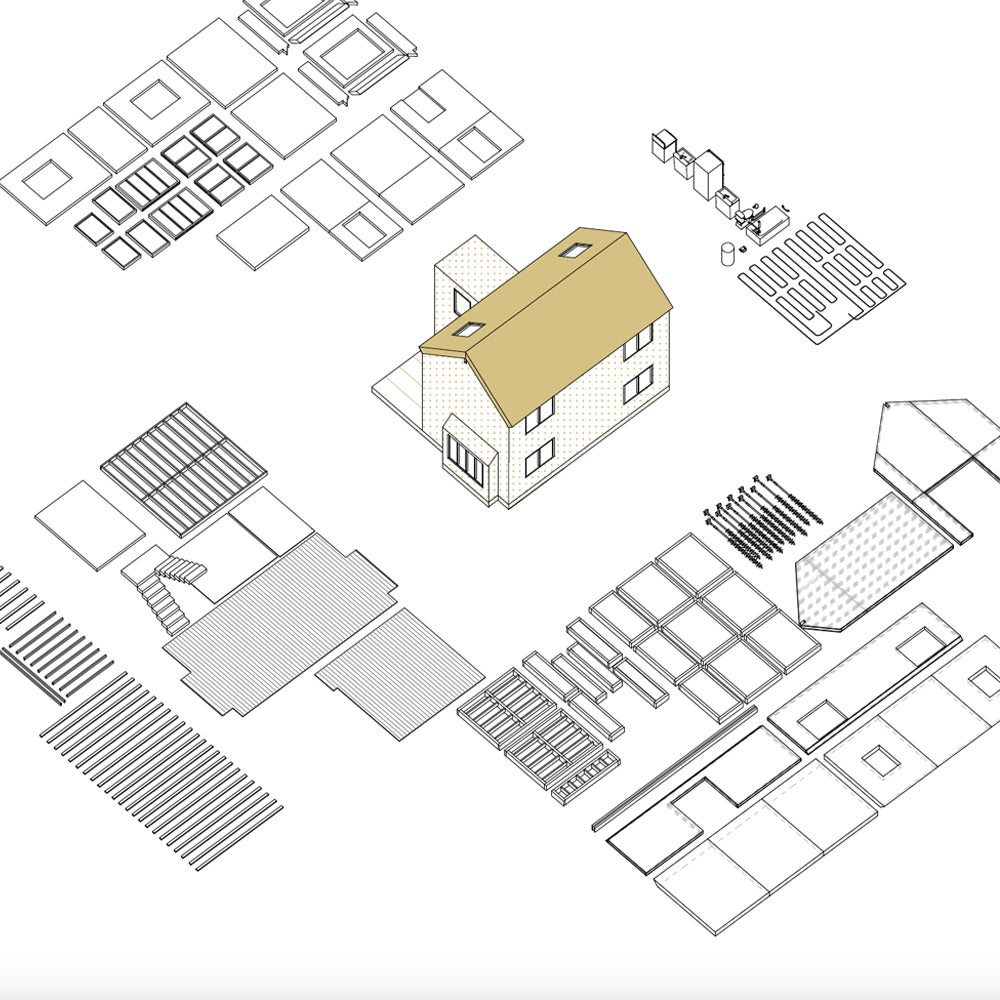

Bringing their design backgrounds to the project, researchers Cho and Jull will also help lead the development of a comprehensive “catalogue of best and emerging practices” for snow and meltwater management in Arctic communities. The resource will identify existing planning and design frameworks for protecting permafrost, drawing on case studies from other cities such as Iqaluit, Canada; Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway; and Yakutsk, Russia.

Synthesizing the findings from best practices and incorporating data from the scientific and anthropological aspects of this research proposal, the team will develop a matrix of design, planning, and maintenance strategies for Utqiaġvik in collaboration with the North Slope Borough’s Department of Public Works, Department of Planning and Community Services, and Department of Capital Improvement Project Management. To aid in this aspect of the research, the project team will teach three travelling design studios, one per year, offered in the School of Architecture to students in architecture, landscape architecture and urban design programs.

“Design studios play and will continue to play a pivotal role in synthesizing, translating, visualizing, and applying the environmental data that will be collected in this project,” Cho explained. “They will also augment and shape research into actionable outcomes that our community partners need. And to make them truly actionable, the design and maintenance strategies will have to be built on the strengths and resources our partner organizations already have and value.”

These studios that will take place over the three-year project period are built on over a decade of award-winning teaching by Cho and Jull in the Arctic through design research studio curricula. For many years, they have taken UVA students to Utqiaġvik to study a wide range of design explorations focused on real-world land-use and programmatic conditions, and that aim to promote ecological and cultural vitality in the context of climate change and urbanization pressures. For researchers and students, the act of returning to the town to learn together through on-site engagement in the community and the field provides a tangible translation of ideas to actions, especially when working together with the residents who live and work in extreme environments every day. These studios, technical workshops and in-situ experimentations will provide hands-on opportunities to test and refine the proposed strategies, enhancing their applicability and effectiveness.

Jull explained: “The Iñupiat have been defining what climate adaptation looks like for thousands of years, and their knowledge sheds light on practices of resilience. At the same time, the people there embrace technology and the benefits of modernization. Through this new EI Climate Collaborative, we have a unique opportunity to merge insight from traditional knowledge with science, design, and technology to create forward-thinking models for permafrost management—pioneering innovative approaches in design, planning, development and stewardship within Arctic communities.”