'Seeing Plants' Course Cultivates Close Observation, Curiosity and Wonder

Each spring, Lara Call Gastinger teaches a course in the Department of Landscape Architecture (LAR 8222) titled Seeing Plants: Observation and Documentation. The courses focuses on teaching students to better understand plant communities by observing them, identifying their defining characteristics, and using different drawing and painting techniques to document them.

We asked Gastinger to elaborate on Seeing Plants, her background as a botanical artist and illustrator, and how her students have learned through the practice of careful documentation. Her reflections compliment this visual essay — showcasing the beauty and care found in seeing and understanding plants.

As part of your course Seeing Plants, you teach students the practice of developing a closer engagement with and knowledge of plants through drawing and painting. Tell us more about this class.

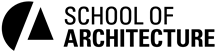

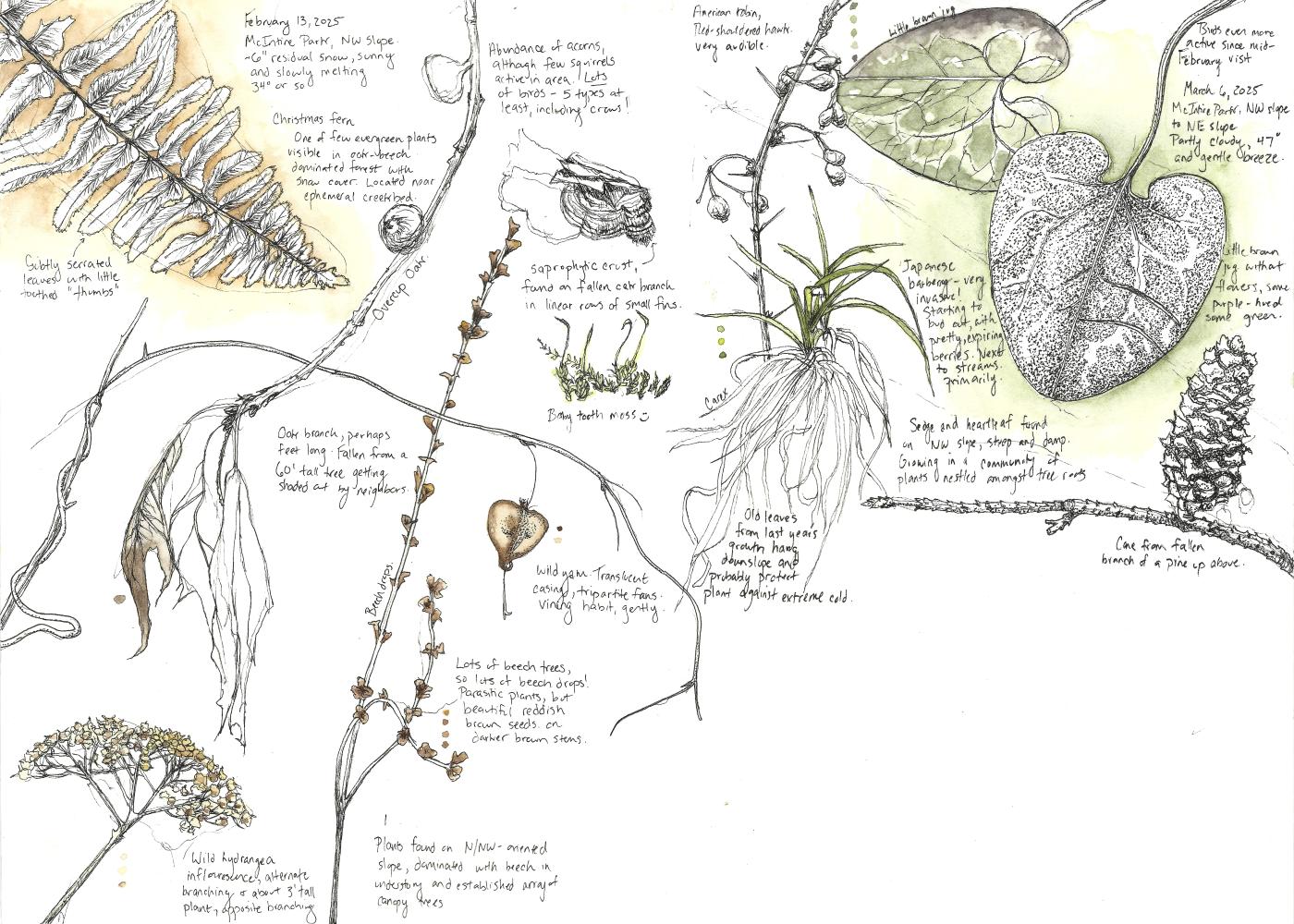

Seeing Plants focuses on a slower pace of observing and interacting with plants. We work at a micro scale, closely looking at bud scales, textures on twigs, and type of leaf shapes, venation, and edges. Throughout the semester, the technicality of the mediums increases from pencil to pen, to one watercolor paint, and then onto a full watercolor palette. This increasing complexity aligns with the arrival of Spring outdoors starting with bare twigs and ending with full color plants. Along the way botanical terminology is accompanied by an increased confidence using the Flora of Virginia app to identify plants.

|

Image

|

Image

|

| (L): Orchidaceae, pen on paper, 10 x 14 inches, Julia MacNelly (MLA '25). Image © J. MacNelly. (R): Twigs, graphite on paper, 10 x 14 inches, Joyce Fong (MLA '25). Image © J. Fong. | |

This course helps to hone skills such as close observation, cultivating curiosity and wonder, and expressing what one sees through accurate botanical drawings. Most students find that they “see” so much more when the walk outside…a curling leaf looks intriguing in ways that it did not before. They also refine their awareness of new changes each day as they start to notice the subtle opening of buds and the herbaceous layer waking up.

How did this practice begin for you?

The practice of observing and drawing nature started for me as a teenager when I attended a summer environmental camp. There, I learned to explore meadow edges and learn plant names from a botanist while learning basic observational drawing skills from a sketchbook artist.

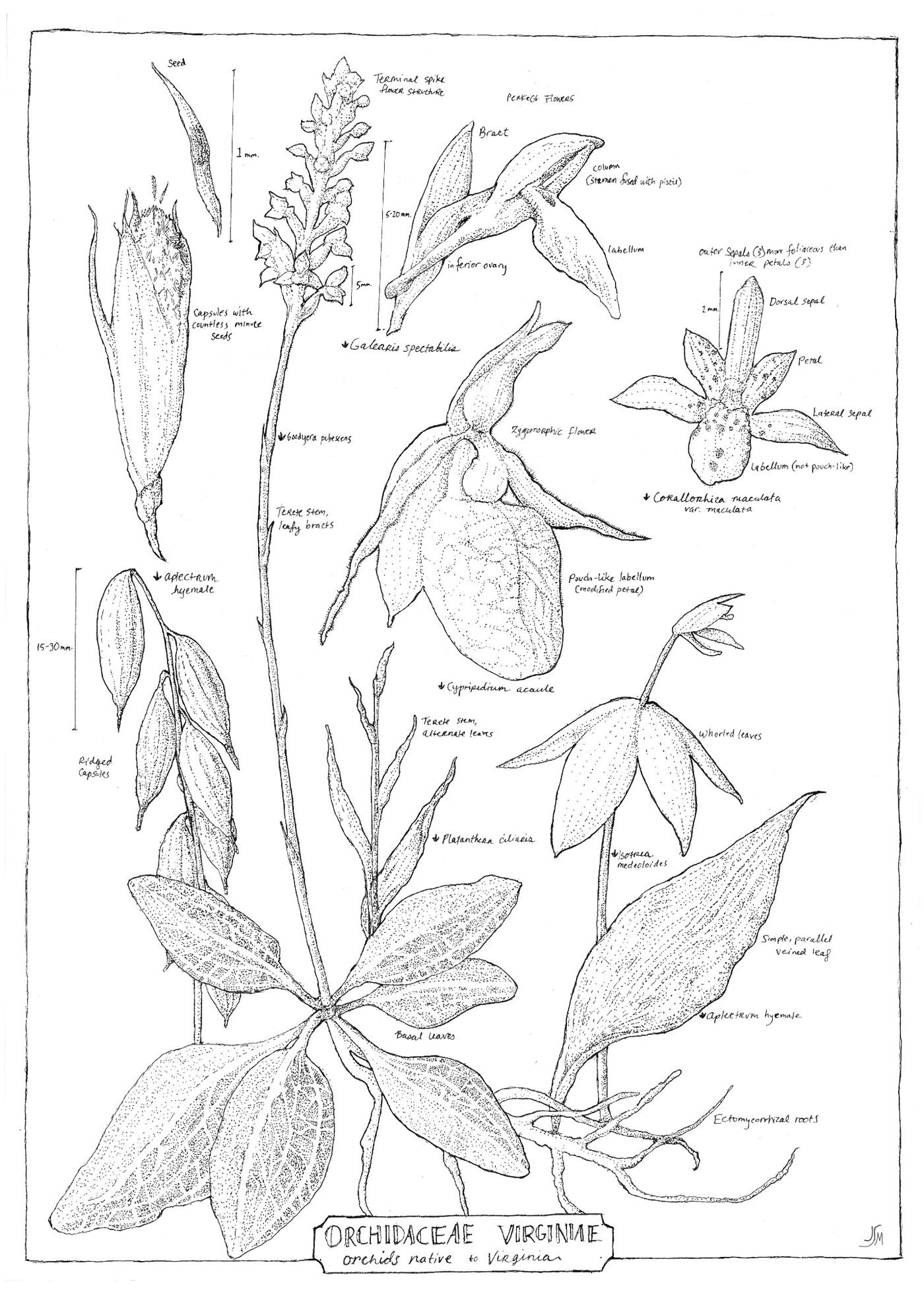

I maintained this interest in drawing and identifying plants throughout my college studies (BA in Biology from UVA and Master’s in Plant Ecology from Virginia Tech). At one point in time, I created a commissioned journal for a client in Charlottesville and drew plant observations from their property each week. I continued this weekly practice of drawing for myself when I created the “perpetual journal”. Each spread in the journal is divided into one week where I add an observation on that date. Over time, a spread will be filled with multiple observations from consecutive years showcasing what I saw that week.

Over time, has your practice, and the way you teach this kind of ‘close observation,’ changed? In what ways and what led to these adaptations?

I think when we all start out drawing in a sketchbook, we want to create perfect and exquisite drawings. Over time, I have realized that this perfection should not be the goal, nor should it be an excuse. Creating drawings that are unfinished, and imperfect are necessary and important steps towards a greater understanding of the plant and one’s own art techniques. There is learning in this process. I have adapted to drawing in the moment while not worrying over the perfection of the finished product. This is what I teach to students — I try to help them get over their insecurities and be okay with making “mistakes”.

|

Image

|

Image

|

| (L): Fruits, graphite on mylar film, 9 x 9 inches, Abigail Millar (MArch '25). Image © A. Millar. Monochromatic Leaf, watercolor on paper, 10 x 10 inches, Adrian Robins (MLA '24). Image © A. Robins. | |

I have also leaned into asking pondering and wondering questions when making observations. There is an immediate desire to learn and name something… it’s Quercus alba (white oak). Yet, a plant is more than its assigned Latin nomenclature. It is more powerful to dive in and ask…. why are the leaves like this/what is happening here/who is living and eating this plant /how is this different than last time I was here/what more can I learn about this….?

What are a few specific discoveries you’ve made over the years of keeping a perpetual journal? What discoveries do you see in your students as they learn to ‘see plants’?

The most interesting observation that I’ve made since keeping a perpetual journal is the change in the bloom times of plants in the Spring, specifically the red maples. When I started my journal, the red maples bloomed in March and now they bloom in early February, and I once observed bloom times of late January! The effects of climate change can be seen within the pages of my perpetual journal.

|

Image

|

Image

|

| (L): Oak leaf, pen on paper, 10 x 14 inches, Sean Alberts (MLA '25). Image © S. Alberts. (R): Forest edge, watercolor on paper, 11 x 15 inches, Lara Call Gastinger. Image © L. Gastinger. | |

In the course Seeing Plants, we create a modified perpetual journal (due to the limited time) and return to a site and make observations each month. It is the same site, but just like in the perpetual journal, the students ask – what is different this time?

They are usually surprised how much has changed within a month. It is also a revelation to discover how much there is to see and draw when you take time to pause and slow down. They also gain confidence in drawing outside, in the elements. The first visit is full of tentative marks, but the page fills up with exciting discoveries by the third visit.

|

Image

|

Biography

Lara Call Gastinger is a botanical artist and illustrator in Central Virginia. She is a lecturer at the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture. Lara was the chief illustrator for the Flora of Virginia Project and a two-time gold medalist at the Royal Horticultural Society Botanical Art Shows in London (2007, 2018). She is renowned for teaching how to create and maintain a perpetual journal.

The subjects of her art come from the natural world and her art reveals detailed evidence of change, decay, and processes that occur in nature. She finds great inspiration in a carrot that has gone to flower, a broken seed pod, twisted roots or insect damage to a leaf.