Cisterns, Collectives, and Cultural Heritage in Urban Egypt

Professors Tessa Farmer (Anthropology, Global Studies) and Phoebe Crisman (Architecture, Global Studies) spent the summer in Egypt where they worked on the collaborative research project “Water Reuse, Urban Agriculture, and Heritage Preservation in Cairo's al-Khalifa Neighborhood” in collaboration with Cairo-based Athar Lina Initiative. They spoke with UVA Global about how sustainability and cultural heritage preservation intertwine in this project and why the co-design process is essential to these goals.

Tell us about the origins of this project. Why were interdisciplinary collaboration and combined expertise central to the project’s design?

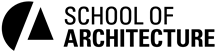

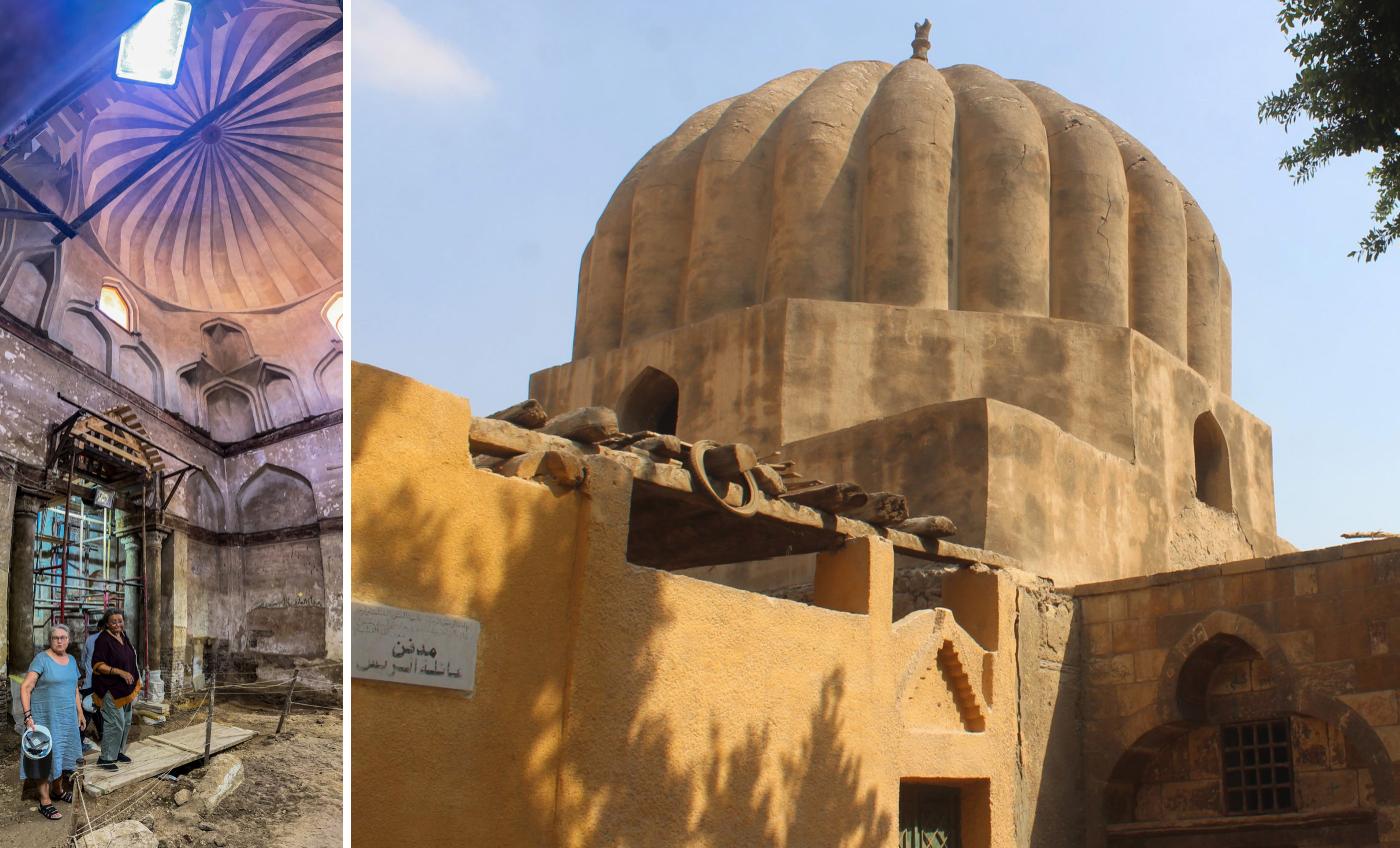

Farmer: The Althar Lina Initiative has been working in the neighborhood for ten years, starting on projects that were explicitly about the conservation of historic monuments, but developing over time into being a multi-prong project to build better relationships between community members and the heritage that they live with. The Initiative has branched out into helping document the neighborhood's intangible heritage and revitalizing heritage hand crafts. Part of the challenge in the restoration work is inundation by water leaking from the potable water system, which creates the counterintuitive problem of an overabundance of water in an arid context. The Initiative is looking at ways to build on their prior work to turn this water into a resource for improving the quality of life in the neighborhood, focusing on urban greening to address the impact of climate change and on urban agriculture to improve access to nutrition. They are thinking about ways to turn what has been considered a problem into an opportunity, but that requires thinking through many material, political, social, and economic questions. Bringing together this interdisciplinary team has allowed us to collaborate in the process of understanding all these complexities in deeper and richer ways through the multiplicity of disciplinary perspectives and enabled us to work with community members and the Initiative to come up with locally viable designs for growing food and making their city more livable.

How do you align the goals of sustainability and cultural heritage preservation in this project?

Crisman: Heritage preservation is often seen as something looking towards the past and reclaiming lost things. An exciting aspect of Athar Lina’s approach is that they are looking at heritage preservation as a generator for contemporary life, as an important cultural asset that has been maintained and needs to find a way to be viable into the future. Moreover, the collaboration is trying to take one of the key problems facing these historic sites, inundation by ground water, and turning this into a resource for a whole new green network.

What is the role of community engagement in this project? How are local residents and stakeholders in the al-Khalifa neighborhood involved in the co-design process and how does this impact the project's goals and outcomes?

Farmer: Through ethnographic research and co-design workshops with community members, the project is working to develop local definitions of the problems that need to be solved and blending local ideas about how to address them with possibilities from the literature and experience of team members. One particular example of this came about when the Initiative realized that the Heritage and Environment Park they worked to create in the neighborhood needed to be programmed to respond to the diverse needs of constituencies within the neighborhood. Women and children need time, space, and activities designated for them, and that meant shifting how and when spaces in the park are used.

How do you envision this project contributing to broader discussions on climate change adaptation in urban areas? Are there elements of your work that could be replicated in other cities facing similar challenges?

Crisman: The principles and process of the project are broadly applicable, but solutions aren’t intended to be replicable. Materially, socially, and politically, solutions need to be locally responsive, so creating models for how to understand particular contexts and thinking through the implementation of solutions that might work (e.g. which native plants might work, or how might shade be created in this location, etc.) are the aims. With that said, in this context the water problems that the neighborhood is facing come primarily from large-scale leakage from the potable water system, so some of what the project creates in al-Khalifa might be applicable elsewhere in Cairo and possibly in other locations with the same kind of municipal water challenges.

What are your future plans for the project?

Farmer: During our time in Egypt, we developed plans to continue collaborating on the Khalifa Heritage Urban Greens Project, and are also exploring joint research and adaptive reuse design projects for a series of medieval and Ottoman era cisterns in Alexandria, Egypt.