Community-Based Design-Build Initiative Explores Affordable and Sustainable Housing in Charlottesville

While it’s unknown who coined the term ‘Accessory Dwelling Unit’ also known as ‘ADU,’ there is a long history of this building type in the United States. In an article titled, “ADUs Are an American Tradition,” the historic carriage house or coach house is described as a precedent for the modern day ADU. “Originally built for horse-drawn carriages, the structures…were frequently large enough to double as living quarters for workers…Decades later, in response to housing shortages and economic needs, many surviving carriage houses were converted into rental homes.”

Following World War II, the rise of neighborhood developments that centered around the suburban single-family home coincided with residential zoning codes that typically limited the allowance of only one home per lot, which meant that ADUs could no longer be built legally by homeowners or developers. Over three decades later, to support smaller and more affordable residential options for expanding housing needs, many cities across the United States began to revisit ADUs as a possible building type with a variety of positive benefits. In more recent years, the increasing cost of housing has driven many cities to revise zoning codes to legalize and encourage the creation of ADUs.

Simply put, an ADU is a small residence that shares a single-family lot with a larger, primary dwelling. Based on size, ADUs are typically less expensive to build than larger, standalone homes, but can often increase property value or generate additional income. They can also take into consideration a larger variety of socio- or socio-economic preferences of residential living such as multi-generational or cooperative housing.

In the last five years in Charlottesville, a considerable rise in housing prices alongside a deficit in affordable housing stock, resulted in the City of Charlottesville creating an Affordable Housing Plan. The plan outlined a series of reforms focused on building, preserving, and maintaining units whose rents are within reach of those with lower incomes. Specifically, four years ago the city council approved both a new comprehensive plan and an affordable housing plan that would increase the number of housing units overall, require inclusion of 10% affordable units in developments of 10 or more homes, and include zoning modifications to increase density. After several months of public hearings and open review, a new zoning ordinance and map was adopted in late 2023 and made effective February 2024.

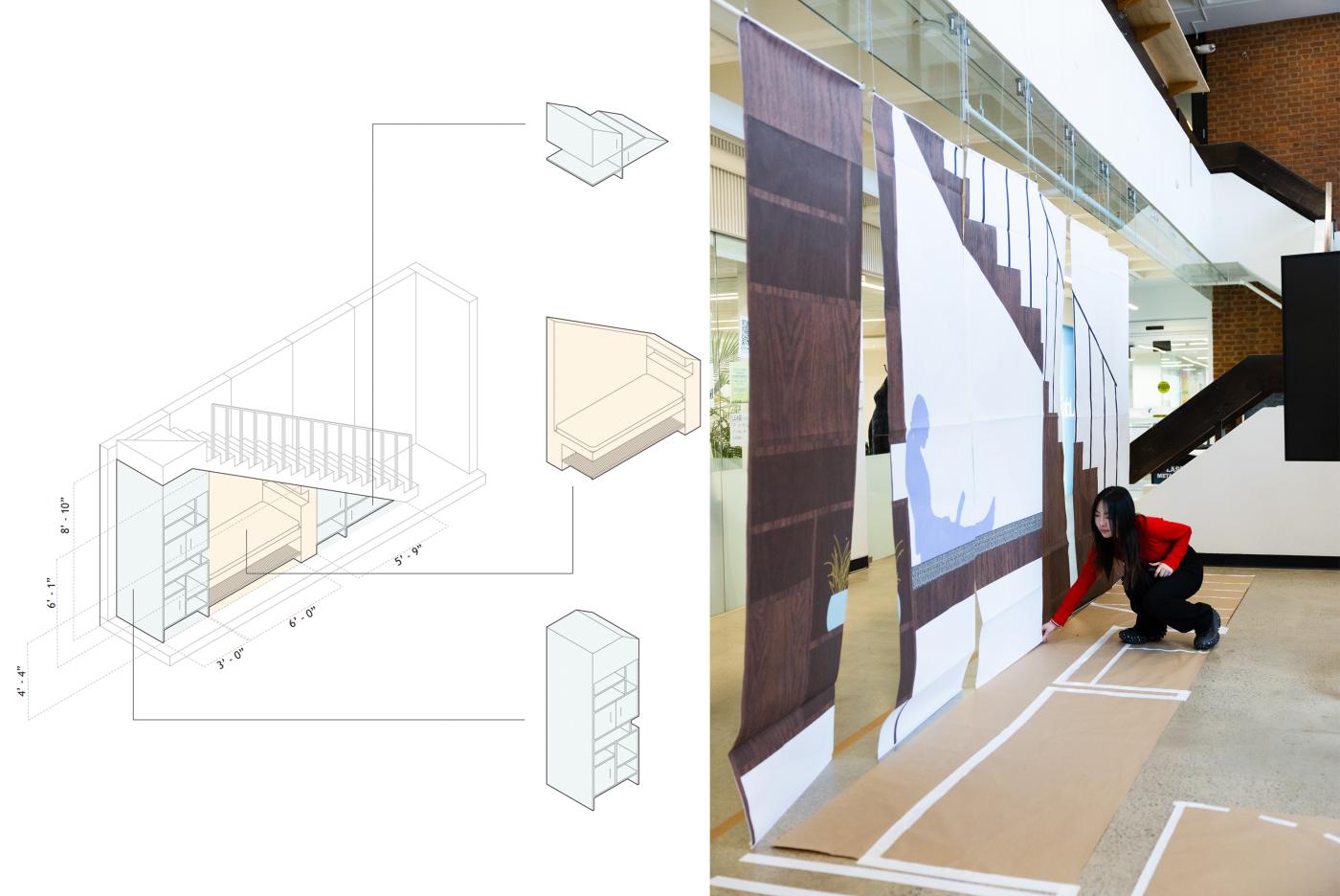

A New Vision for A Suburban Kit of Parts

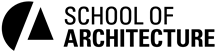

In response to the City of Charlottesville’s recent zoning ordinance and their commitment to affordable housing, a group of faculty and students at the UVA School of Architecture are working on a multi-year project alongside the city and community organizations to develop a systematized approach to housing that proposes an alternative to the post-WWII suburban model of residential development. Exploring the potential of ADUs, an advanced research studio (held in Fall 2024) co-taught by Assistant Professor of Architecture Schaeffer Somers and the Environmental Institute’s Practitioner Fellow Bobby Vance invited students to develop design ideas for small housing units.

“[By adding smaller units on a single lot] you can start to create ‘cottage courts,’ or a kind of ‘missing middle’ compound of smaller dwellings,” said Somers. “This is the problem that the studio was able to investigate.”

Undergraduate and graduate students in the studio developed their proposals alongside feedback from local community organizations, such as Habitat for Humanity of Greater Charlottesville represented by alumni Amanda Harlow and David Schmidt. Representatives from the city, including Deputy city Manager for Operations James Freas and Director of Neighborhood Development Services Kellie Brown, generously participated in classes presenting invaluable information to students about the local context of housing in Charlottesville. Local builder Bill Jobes (Jobes Builders), architect Kate Snider Tabony (Oak Five Architecture + Landscape), and landscape architect Shanti Levy (Red Clay Landscape Architecture), joined student-led presentations, sharing insights in response to research and ideas presented by the students. Throughout the semester, the studio adapted to input from the community and practitioners—incorporating lessons learned and developing proposals generated by understanding community needs.

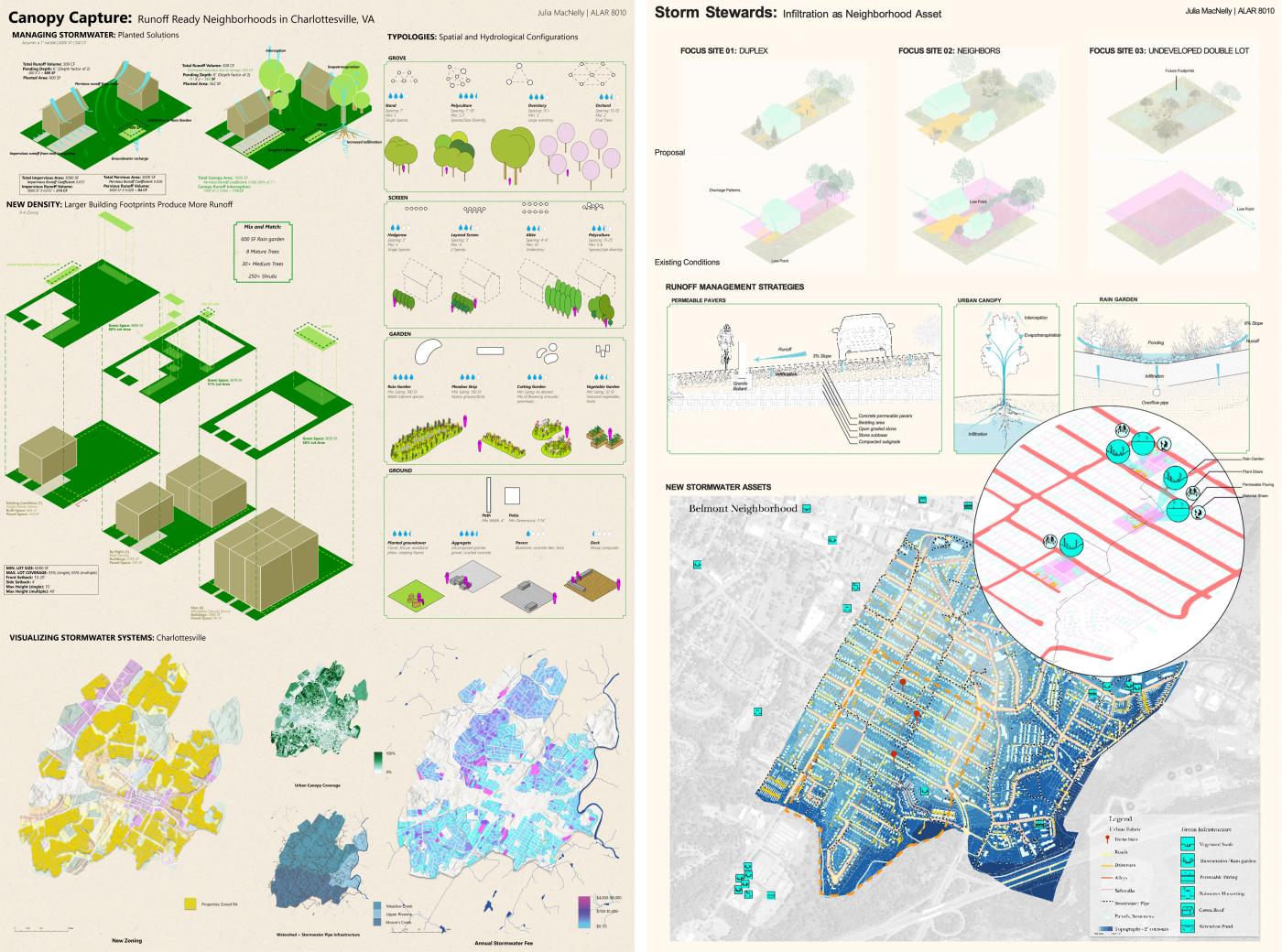

The studio’s goal, which will continue to be developed over the course of the next several years, includes the creation of an ‘ADU Kits of Parts’, or a systemized set of components or prefabricated assemblies that could be both ‘permit-ready’ or pre-approved by the city, but also customizable for a community partner, or even eventual residents. To design these ‘parts’ to work together, students took many building and material variables into consideration including cost, lifecycle, environmental factors, and aesthetics.

In parallel to design and building considerations, Somers is teaching a Health Impact Assessment course in the Department of Public Health Sciences, in which Master of Public Health and Global Studies students are exploring the unintended health consequences of increased housing density which often extend beyond the interior spatial footprint of a housing unit. For example, building more units can reduce tree canopy and increase the need for impervious surfaces, and lead to negative health outcomes.

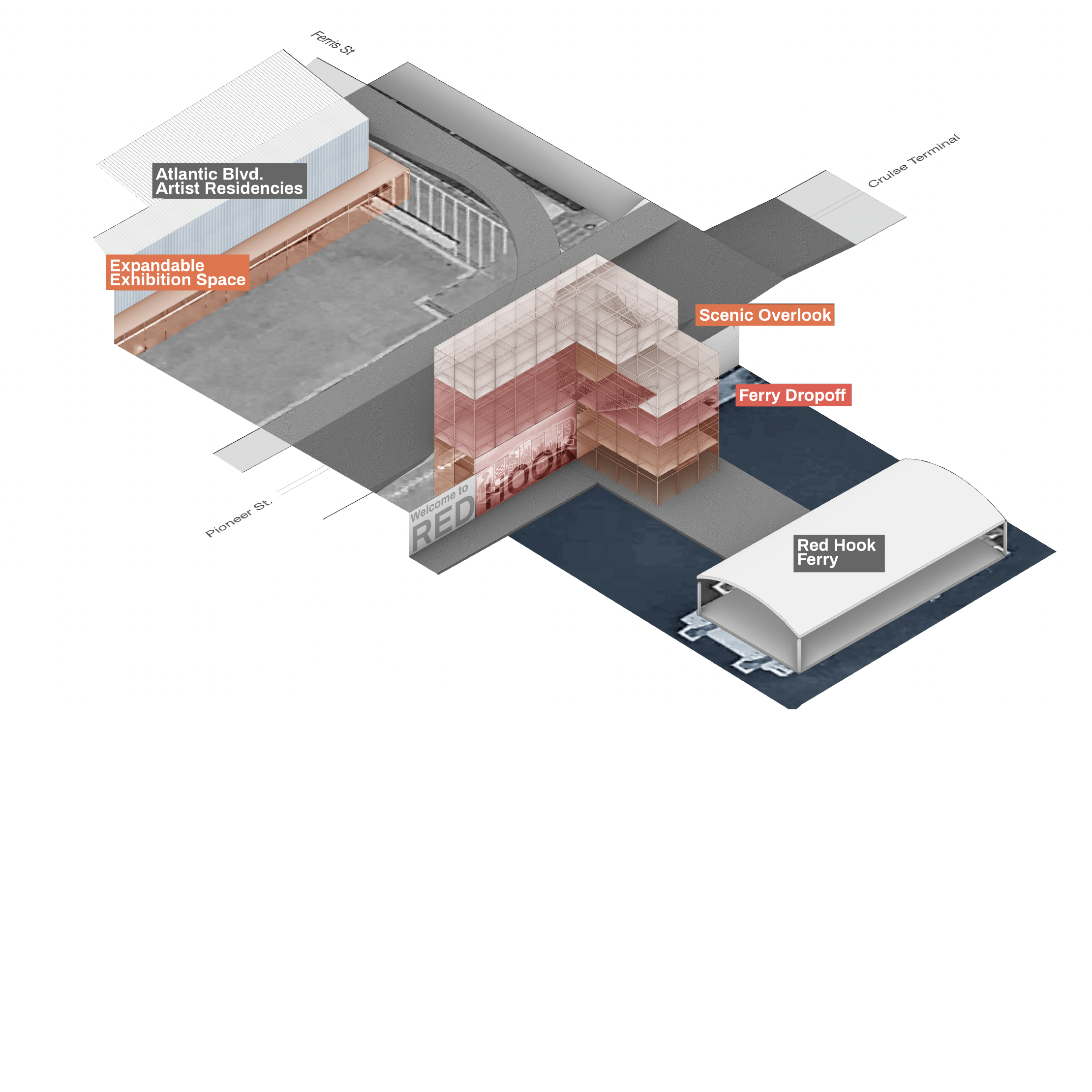

Julia MacNelly, a graduate student studying landscape architecture, took a deep dive into residential living in Charlottesville beyond the house itself—carefully investigating the residential lot, exterior space, and how landscape design could contribute to innovative resource management. As a part of a much larger comprehensive analysis and proposal, MacNelly researched and presented the potential benefits of managing stormwater through plant material at the scale of an individual residential lot, proposing green infrastructure alternatives for the city. MacNelly developed a different kind of kit-of-parts that outlined a variety of customizable planting schemes taking into consideration budget, topography, soil conditions, saturation tolerances and more—all part of an effort to increase tree canopy coverage and maximize planted groundcover for the filtration of water. Somers and Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture CL Bohannon are currently working with MacNelly to extend her work in partnership with the city and Piedmont Community Land Trust (PCLT).

Overall, students and faculty sought to find innovative, yet practical and actionable, ways to rethink the standard American suburban model in a community challenged by affordability and climate change. The studio raised important economic, social and environmental questions about ‘home’ — What is the right size needed for a dwelling? How can a starter home grow or shrink over time as needs change? What resources needed for a home, its lot, and occupancy, can be reused or recycled? What efficiencies can be designed to lower costs, while maintaining quality, comfort and wellbeing?

“The house and the design-build model are great vehicles for experimentation and actionable research,” Vance explained. “We can invite others from around the University and the community to say what we want this [dwelling] unit to test and then solicit feedback to continue to improve the project.”

A Design-Build Pedagogy Addresses Community Needs

Building upon last fall’s research studio, Somers and Vance are developing the next steps to realize a larger vision for a design-build program to address Charlottesville’s, and the Commonwealth’s, housing needs with a focus on energy efficiency and affordability. As a Practitioner Fellow for UVA’s Environmental Institute, Vance is working on creating a roadmap on how to develop successful and long-term partnerships across academia, industry and community to realize design-build initiatives. Vance brings his experience as the Competition Manager for the Gateway Decathlon design-build competition and exhibition to this effort. The Gateway Decathlon challenges multidisciplinary university teams to demonstrate innovation in design and construction of housing. For the Commonwealth of Virginia, Vance is excited about the opportunities to bridge across institutions and work with local industry partners, particularly in modular design and component-based manufacturers.

“It’s not just pre-approved plans. We are drastically reducing the amount of time it takes, and money it takes, because you are not spending money on permits and design fees. So that is what I’m looking at for the Environmental Institute — how to reconfigure the industry-partner network ecosystem,” said Vance. “Within Charlottesville, and within UVA, what does it mean to have a design-build program, and who are the groups that would be supporting such an endeavor? How do we come together to build something that is unique and special for this place?”

Successful design-build programs established at academic institutions are not new and there are many precedents found at architecture schools across the country. In fact, the University of Virginia has a long history of such award-winning programs, from former professor John Quale’s ecoMOD houses (established in 2004) to former associate dean Anselmo Canfora’s Initiative reCOVER (founded in 2007). While at UVA, Quale led the ecoMOD project for a decade, working with nearly 400 architecture, engineering, landscape architecture, planning, business and historic preservation students on designing and building a series of environmentally responsible and highly efficient housing units for affordable housing organizations. Canfora’s reCOVER initiative also grew design-build programs at UVA, focused on disaster relief. The team’s ‘Breathe House’—designed and constructed by students and faculty, with community partners—provided critical relief housing in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

The current design research on ADU housing takes advantage of Director of Information Technology Eric Field’s long contributions to the ecoMOD program and his role in creating the Social Economic Environmental Design (SEED) Network. In partnership with projects led by Associate Professor John Comazzi with Charlottesville’s Parks and Recreation and Associate Professor CL Bohannon with NuFarm, the ADU program is reviving this rich legacy at the school, while adapting it to current contexts. This work is emerging as part of the Community Research and Design Lab (CRADL) led by Somers.

By focusing on small-scale constructions, students gain a unique experience of taking design ideas to assembly, incorporating community feedback. The real-world application of design-build projects, and being able to engage with community members, is especially meaningful for students.

Vance described, “We often tackle big, important challenges, but we don’t always break them down into real, practical solutions. Traditionally, students haven’t had the chance to build their studio projects, but we’ve come to realize there’s a strong desire to go beyond design—to actually create, craft, and bring their ideas to life.”

As part of the lab, the collaborative framework may look a little different than previous models of academic design-build. Somers explained, “Our approach focuses on “design assembly” in which students are assembling factory-build components on site with community partners.” This engagement with individuals and organizations outside the university remains central to the goals of this project and other design-build initiatives. “There is enthusiasm from students to work with communities,” Somers elaborated. “In fact, in some ways, this aspect of learning from and with others is the most important priority for them.”

Dwelling Advanced Research Studio (Fall 2024) Students

Vaibav Badri (MArch '24)

Josephine Blount (MArch '25)

Emily Carroll (MArch '25)

Alex Cuenco-Olaya (BSArch '25)

Daniel Donofrio (BSArch '25)

Feiyang Liu (BSArch '25)

Julia MacNelly (MLA '25)

Emily Phan (BSArch '25)

Abby Teague (BSArch '25)

Sarah Tyner (MArch '25)

Community Research and Design Lab (CRADL) Student Research Assistants

Amanda Addison (MArch '27)

Sanika Mate (MUD '24)

| Source: ADUs Are an American Tradition (https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/housing/info-2019/adus-are-an-american-tradition.html) |