ADVANCED RESEARCH STUDIO LED BY DAWKINS AND SHIVERS EXPLORES CLIMATE ACROSS MULTIPLE SCALES OF SPACE AND TIME

Hot Blue is a Fall 2022 advanced research studio (ARCH 4010_4011 / ALAR 8010) taught by Marantha Dawkins and William Shivers that probes how the built environment can play an active part in larger climatic, ecological, and urban systems. Focusing on the US Virgin Islands, the studio asks students to contend with climate as "an outcome, not a given" shifting the discussion of global warming from a matter of scarcity to an abundance of energy that can kick-start landscape futures (Dawkins, Cantrell).

Dawkins and Shivers present climate as not "simply a series of facts...[but] also a cultural and interpersonal phenomenon — one that informs conflict, territorial expansion, and community." The research studio centers design as an intentional agent in the ways that environments will grow and change, and how they will degrade and complexify over times and scales.

Through a Q+A, Dawkins and Shivers, both currently PhD in the Constructed Environment candidates, share with us how this studio came to be, while highlighting their students' work and the diverse ways this work takes on issues of long-term resilience in the face of extreme climate change.

CLIMATE ABUNDANCE + MATERIAL REALISM

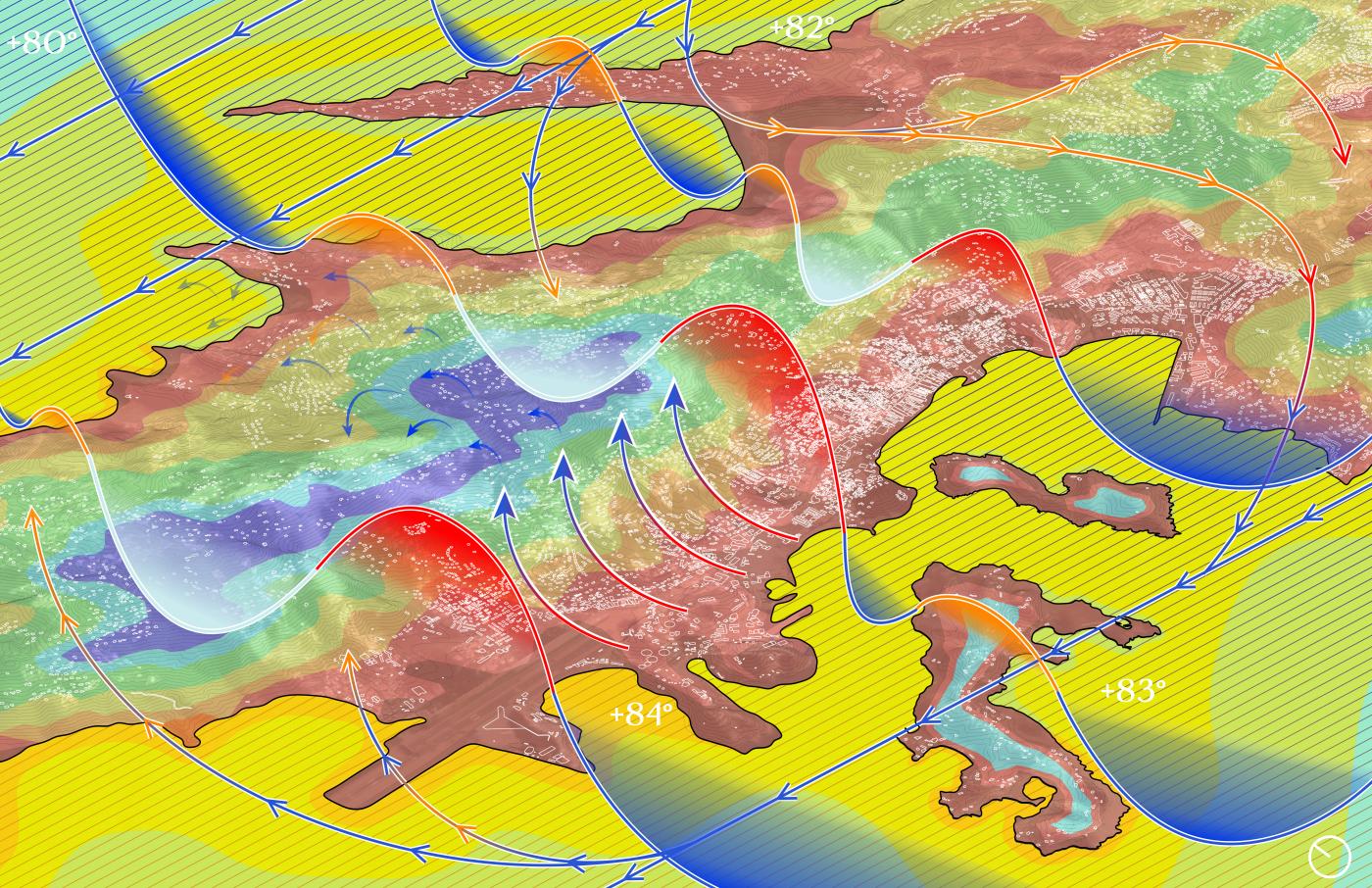

Q: This studio frames climate change around an idea of abundance. You ask: Instead of planning for disaster, how do we design for abundance of force and abundance of material? Abundance takes many forms within the framework of a changing US Virgin Islands: from higher temperatures, to more intense freshwater inundation, to increased debt in the tourism industry, to larger waves. How have students formulated design ideas that engage "abundance of energy" as a means towards opportunity?

A — Dawkins:

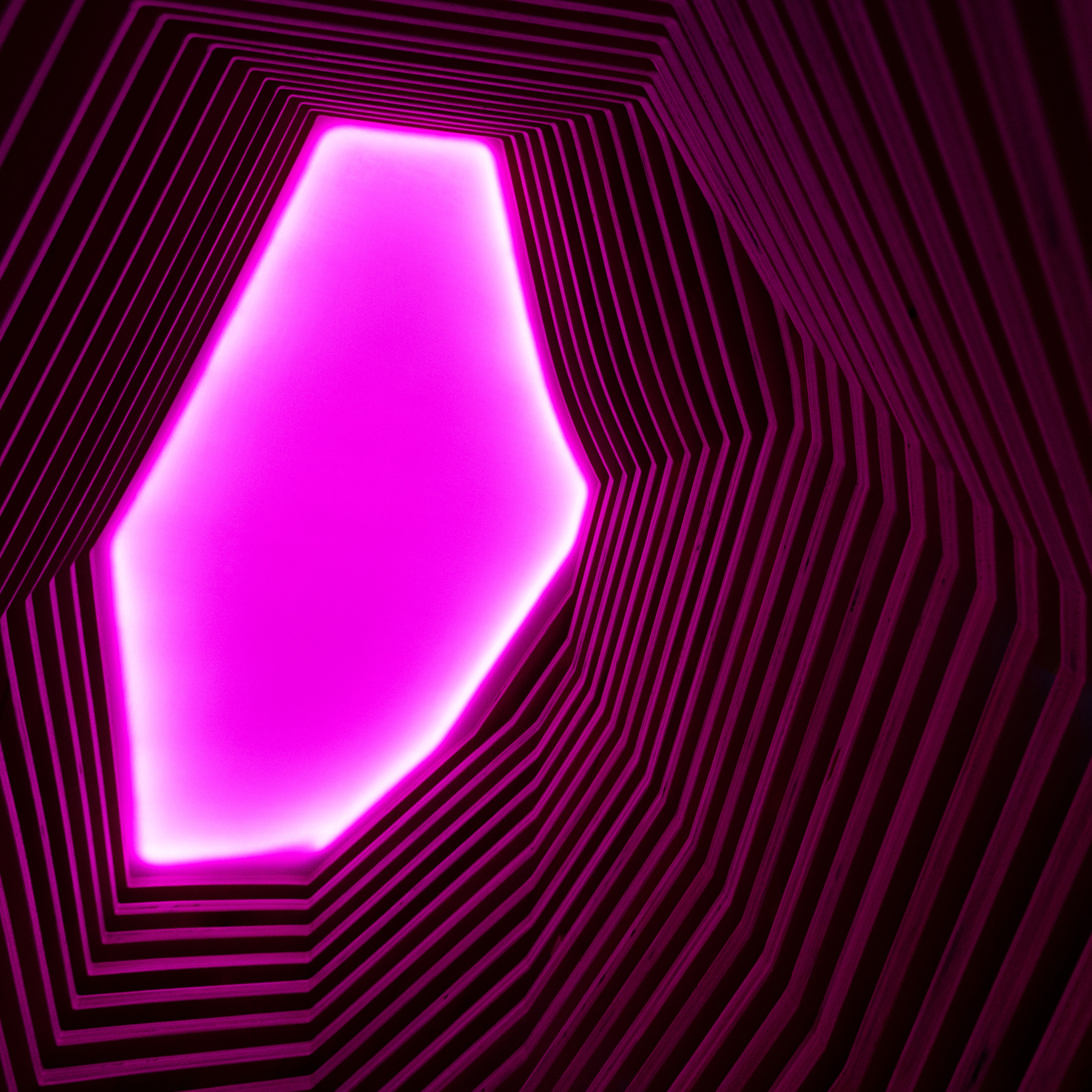

Climate change is often framed as a crisis of scarcity, or of extinction. It is… but by flipping this on its head, by inquiring into new realities rather than lost ones, the students can grapple with and chew on material reality. Things and not lacks. Rather than, for example, framing the increasing frequency and intensity of hurricanes as a loss of a current way of life or a cruel uncertainty, students Ashley Kim and Larry Utter are shaping their work around shelter and community; designing a community center cum storm shelter that take cues from hurricanes like Irma – 425 miles wide, traveling West, with wind speeds up to 180mph, and endangering at least 80 local families – to inform roof slope, storage volume, orientation, etc.

More generally, our students have been working with real climate projections, identifying active research that resolves larger climate concepts on the ground, and using these phenomena as design prompts. Change here works as a generative force.

A — Shivers:

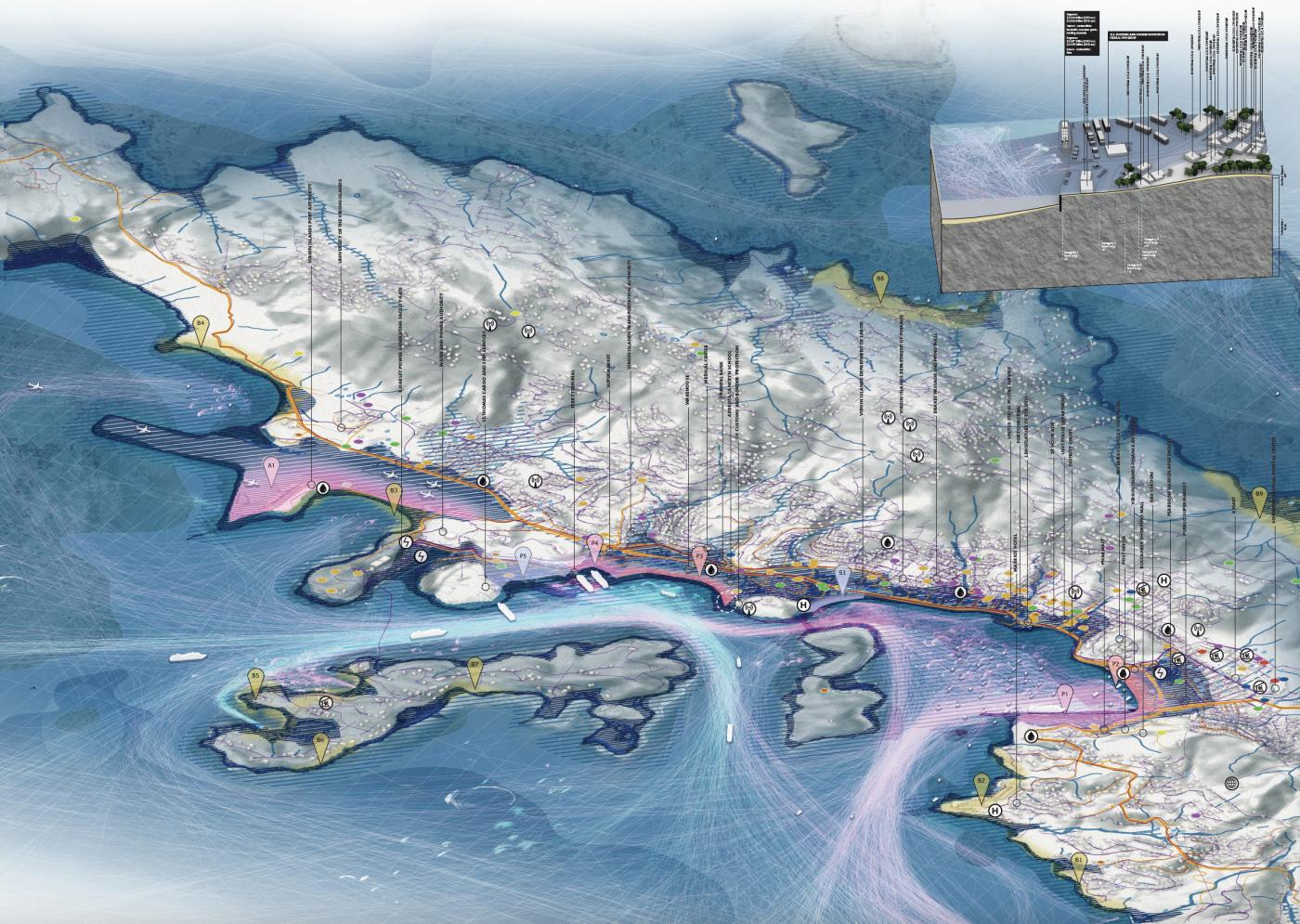

Energy and force takes many forms. Some are visible, others hidden, perhaps even unseen. Yet they are all felt in one way or another. Our students are working with a series of forces (storms, water systems, oceanic tides, heat, and economy) to frame their project and understand how they can work with these phenomena. These many forces have lead to an amazing range of projects that include a new waterfront public infrastructure based on cooling, a housing system which responds to rising sea levels, a localized disaster shelter and civic system, integrated urban and island water processing center, sugarcane energy factory, and a wet research and visitor center.

Q: Hot Blue embraces localism and material realism, exploring design that empowers local response to local communities. How have some of the student projects engaged localism in distinct ways?

A — Dawkins + Shivers:

Undergraduate architecture students Taylor Brown and Emily Rong are designing a cooling center, an emergent form of civic infrastructure. It is a waterfront pavilion with multiple cooling strategies – from shade, to evaporative cooling, to conditioned interior space – that will be critically needed in a much hotter daily life on St. Thomas. Their project lands the abstraction of global heat in the bodies of residents and on the streets of the city, working to address issues of climate change as matters of public health.

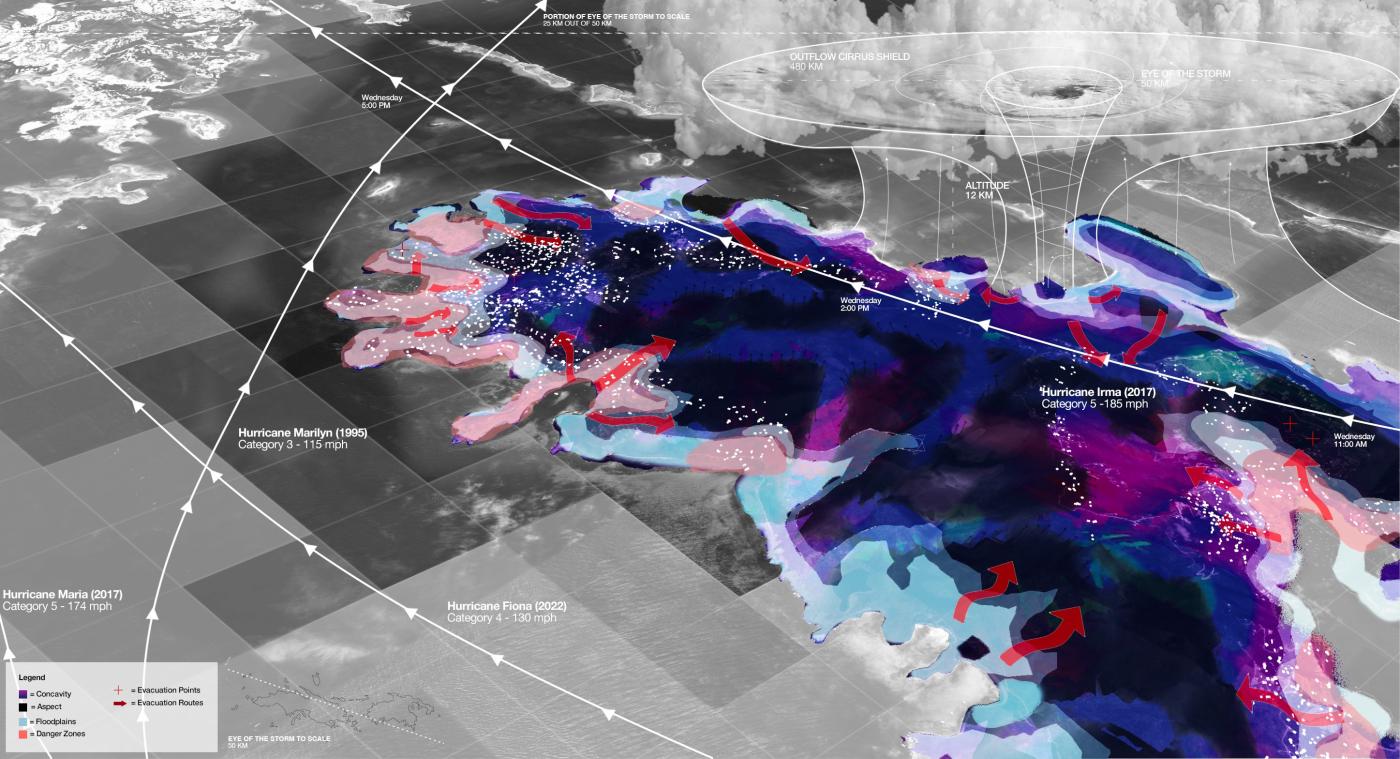

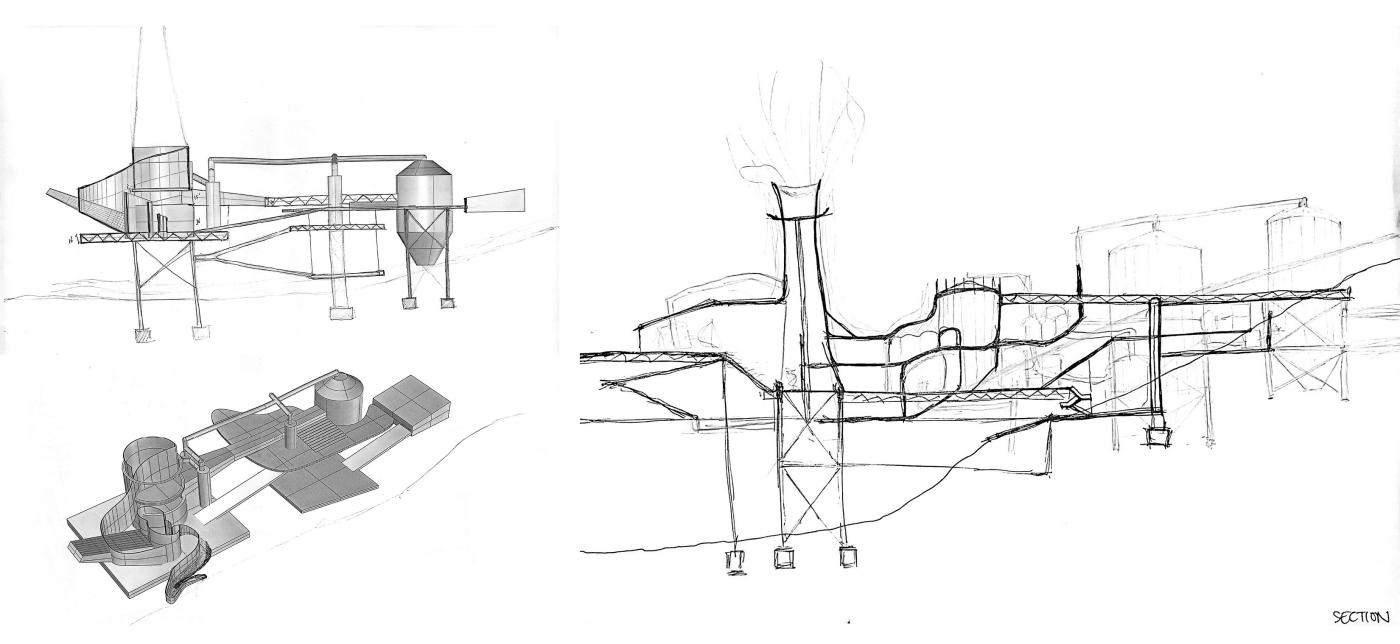

Irem Cetin, a M.Arch. candidate, is focused on the economy of the US Virgin Islands, from their current dependency on the mainland (the islands import 99% of their food, for example), to their tourist economies, to their legacy of sugarcane production. Her project is a wild factory powered by sugarcane by-products and the spectacle of industry, becoming a new center of tourism that creates inter-island economic loops. In her proposal, the consumptive tourist economy is threaded into new forms of production.

INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN TEACHING + RESEARCH

Q: How has the studio so far influenced or challenged your current PhD research (learn more about Shivers' research here and Dawkins' research here), or the longer trajectory of your scholarship?

A — Shivers:

The studio has allowed for an opportunity of and space for shared opinion and thought. Working alongside our students, studio has helped to envision what our research can contribute to and how — being inherently multidisciplinary, the applied research can take the form of a new urban plan, a civic architecture, landscape strategy, or unique detail; all of which can materialize a critique of policies or practices and imagine a recalibrated future. For me, this approach has allowed me to focus on one of my research case studies and actively engage with designing and imagining these futures, which I hadn't previously been able to do in such depth.

A — Dawkins:

Architectural form opens up new kinds of temporality, and it forces a kind of specificity that has unstuck some of the abstractions of climatic design for me. I’ve been thinking at much larger space and timescales recently. Hydrological and geomorphological time, in particular, have a very different cadence than everyday, human life that makes it easy for me to fall into a sort of formal laziness. By working with our students on real design details, experienced at a range of scales (from the movement of a drop of water, to the treads on a flight of stairs, to orchestrating an 8-degree temperature drop, or preparing for a rising sea) — this has been pretty great. Rather than conceiving of works at this scale as blips in the face of immense, uneven change, it’s been wonderful to look at them as ways of binding energy into larger climatic systems, as promoting niches for life that can scale down infinitely. It’s been very influential.

Q: What has team-teaching been like? What unique perspectives do you each bring to the studio and as well as a pedagogical approach?

A — Shivers:

Teaching together has been a very exciting and rewarding experience so far. Our work has aligned since our start in the PhD program in 2020, yet we come from very different backgrounds. We overlap on many key topics, but approach the work from sometimes opposing perspectives, which highlights the breadth of opportunity in engaging with issues of climate through design. Marantha brings an incredible rigor and critique towards climate metrics and forces that help articulate the gravity of the climate crisis, but also has a keen eye for how even the smallest detail in a building’s design or public space’s strategy can enact change. In her rigorous approach, she also weaves in a bold imagination that integrates sci-fi novels, movies, and projects that maintain an essential fun.

A — Dawkins:

Uncertainty is a big part of climate futures. There isn’t one picture, or one value, or one answer: working speculatively always involves navigating a range. The conversations that Will and I have between ourselves and with our students creates ranges of possibility. This range is productive.

THE CLIMATE DETAIL

Q: What is an unexpected or experimental method/approach used within the studio that has opened up a different way of understanding climate change?

A — Shivers + Dawkins:

We created a studio that was built for students studying across disciplines at the School — architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning. What has been surprising teaching a studio of all architecture students, has been how they are all taking a baseline core curriculum and approach to explore and ideate through very different methods.

Currently each student is working towards designing a "climate detail" — they are understanding and designing how their building responds to greater climatic forces, and how site-specific design details are part of that response.

Across the class, the climate detail work has wrangled large climate issues into wall sections, into flashing, wastewater pumping systems, and more. The resolution of this exercise has helped open up new ways of understanding what climate change is, how it works, how it can be lived.

For example, graduate architecture student Brandon Dennis is working on a flood-able house with interlocking pieces that assemble into floating wholes, resilient to the upward creep of the sea. His interest in this building assembly crystallizes a future, he imagines, of roommates and shared costs. Less children, less permanence. All baked into an expansion joint.

Each student has worked in bold methods of representation where we have encouraged them to break typical conventions we see and expect. Climate intensity is always represented in bold color gradients or intense graphics, so why shouldn’t our design work be equally radical?

ARCH 4010/ALAR 8010 - HOT BLUE STUDENTS

Teo Abrahao-Blazquez

Tamar Ayalew

Francis Joseph Becker

Taylor Brown

Irem Cetin

Brandon Dennis

Ashley Kim

Rebecca Nordt

Emily Rong

Larry Utter