Adaptive Shelter Healing Landscape: Earl Mark's Studio on Designing for Displacement

Earl Mark, Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of Virginia, has extensively explored the intersection of design, technology, and humanitarian response. His spring 2025 advanced research studio, Adaptive Shelter Healing Landscape, is sited in Acadia National Park in Maine—continuing a series of National Park-focused studios he has led since 2007. The course challenges students to develop shelter solutions for forcibly displaced people, balancing immediate needs with long-term adaptability. Drawing on a current research collaboration with a humanitarian shelter and settlement group, Mark emphasizes Shelter as Process, a best practice methodology that prioritizes pliancy and the agency of displaced people. In this conversation, he reflects on the evolution of the studio, the role of material experimentation, and the potential for architects to engage meaningfully in global displacement challenges.

Designing for Displacement: A Process-Driven Approach

Your studio challenges students to design for forcibly displaced communities, balancing immediate needs with long-term adaptability. How do you guide students to think critically about the lifespan and evolution of temporary structures?

EM: A defining aspect of the studio methodology is the concept of Shelter as Process. This approach, advocated by humanitarian practitioners since the 1970s, is now widely recognized as the most viable method for large-scale shelter response. A current collaborator Joseph Ashmore, a highly experienced expert in Shelter and Settlement Response at the International Organization for Migration (IOM) at the United Nations, introduced a process-oriented approach over a predefined shelter design to prioritize greater adaptability to specific conditions and community needs.

While emergency situations may require pre-designed shelters, a much-preferred approach involves establishing a participatory process that integrates the direct agency of displaced people in the making of shelter. This necessitates more variability in the architect’s role from a traditional designer to a designer of process—or even stepping back entirely to become an enabler. Adaptation, collaboration, rapid decision-making, and risk assessment are critical components of this process. Moreover, actively engaging residents in the design and construction of their shelters is increasingly recognized as an important part of psychological recovery from displacement trauma.

The most successful strategies empower displaced communities to actively shape their surroundings in response to evolving needs.

In the studio, students follow a structured design process similar to other architecture courses, but with an added layer of real-world complexity. They must not only develop an adaptable shelter system and consider the lived experiences of displaced people but also promote their agency for self-determined solutions. Without the time to conduct direct sociological fieldwork in one semester, each student independently proposes and researches a displaced community narrative and applies their insights to our studio site at Acadia National Park on Maine’s Schoodic Peninsula. Students critically analyze andn compare each other's approaches. This methodology helps them understand both time and resource constraints and opportunities inherent in designing for displacement.

Evolving the Studio in Response to Global Displacement

Given the scale of global displacement today, how has your approach to teaching this studio evolved since you first offered it in 2007?

EM: The first studios in 2007 focused on adaptive fabric structures with a small environmental footprint for National Park settings, offering an alternative to brick-and-mortar buildings. Students explored protected sites across Maine, envisioning temporary stays for groups like disadvantaged children.

My perspective shifted dramatically in 2015 when I witnessed the Syrian refugee migration firsthand. Traveling from Budapest to Vienna, I arrived at a train station where families—many with young children—were spread across blankets on the floor. The scene, ironically reminiscent of families at a crowded beach but in far harsher conditions, left a lasting impression. The children’s innocence contrasted with the adults' visible uncertainty and worry.

Initially, I naively believed it was possible to design better shelters for displaced people. However, through learning from humanitarian organizations and visiting refugee camps in Greece, I realized the complexities of aid work. This led me to join UVA Professor Peter Ochs' Religion, Polititics, and Conflict group, which provided an evidence-based framework for evaluating conflict and displacement.

The studio has since evolved to incorporate these broader insights. Students now examine shelter and settlement strategies within a three-stage framework—emergency shelter, community-driven adaptation, and long-term reconstruction—originally outlined by Ennead Lab architects Don Weinreich and Eliza Montgomery. Their 2019 talk at the School of Architecture highlighted the risks of externally imposed solutions, such as the failed post-earthquake condominium housing in Haiti or the rejected barracks-like shelters replacing makeshift structures in Calais, France. These case studies reinforce why flexibility and community participation must be integral to design. By grounding their work in these principles, students can better anticipate the evolving nature of displacement and settlement processes.

Material Experimentation & Hands-On Learning

Your students begin with hands-on exercises using simple materials like stretch fabric and kids' jewelry kits. What role do these early experiments play in shaping their design process?

EM: Although I have significant expertise in software engineering and teaching 3D computer modeling and visualization systems for architecture, I’ve always found it essential to work by hand with real materials and learn from experienced fabricators. Fabric architecture shapes have long fascinated me, as they can be self-supporting with just a few control points—a concept students grasp through hands-on experiments. A simple saddle form, or “hypar” surface, can be shaped using only four points, creating a distinct aha moment. I demonstrate this on the first day by having students make forms with double-stretch fabric at human scale before progressing to more complex forms.

While fabric architecture techniques are not unique to this studio, the malleability of tension membranes is central to our approach. Students begin by shaping fabric by hand rather than relying on computer models or precedent studies. The jewelry kit technique, refined by students in a 2016 studio, influences this hands-on method.

During your recent trip to Maine, students engaged with local industry experts. How does understanding sailmaking translate to designing flexible, fabric-based shelters?

EM: A key aspect of the studio is learning from experts who work with relevant materials. Sailmakers, for instance, refine fabric reinforcement and structure to optimize performance. The subtle geometric camber of a sail directly informs how we shape tensioned shelter forms.

This spring, we visited a sailmaker who uses traditional techniques for contemporary reconstructions of wooden boats, such as schooners and sloops. A wooden boatbuilding workshop offers insights into wood properties, weathering, and shaping double-curved surfaces using techniques like Carvel and Lapstrake planking. While some of this can be simulated on a computer, handling actual materials is far more informative. One student was so inspired that she enrolled in a boat-building school on the West Coast after graduation.

|

Image

|

Image

|

|

Image

|

Image

|

| Clockwise from top left: students use spandex to create a single saddle fabric model, January 2025 (photo: Earl Mark); first model assignment for Adaptive Shelter Healing Landscape, Spring 2025, by Zoe Hall; a mast hoop created during a steam bending and fabrication workshop, Maine studio trip, 2016 (photo: Earl Mark); mast hoop workshop, March 2025 (photo: Earl Mark). | |

Site, Environment & Well-Being

What parallels do you see between the environmental vulnerabilities of the Schoodic Peninsula and the challenges faced by refugee settlements worldwide?

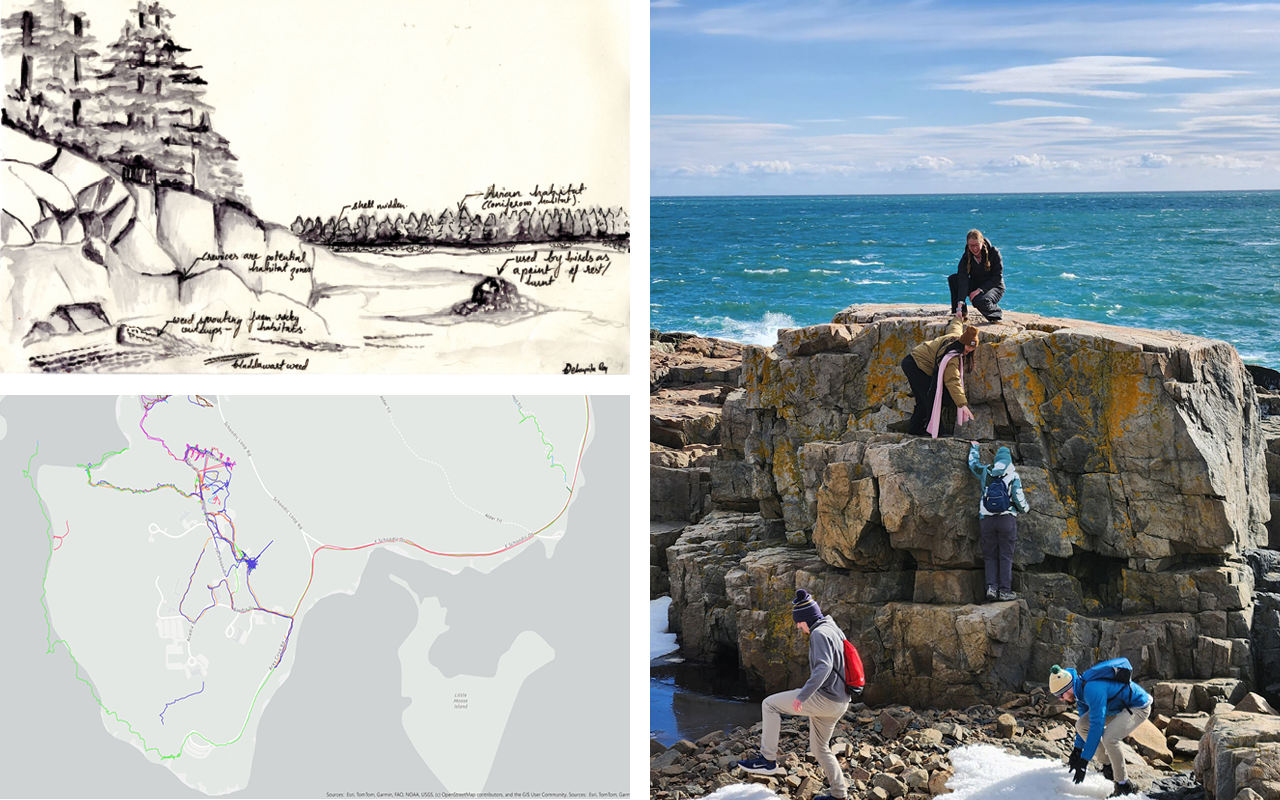

EM: Rising sea levels and storm surges have had a tangible impact on the roadways of Schoodic Peninsula. Storm damage, first evident in 2007, appears even more severe today, with frequent “blowdowns," trees with shallow, wide-spreading root systems, upended entirely and rotated perpendicular to the ground. During our field trip, we also learned about an alarming rate of species migration. Invasive plants, trees, and animals are increasingly prevalent, while other species are either moving north or in sharp decline, including marine life.

This migration, with some species facing extinction, serves as both a mirror and a metaphor for forcibly displaced human communities. It provides a meaningful prompt for the studio’s design program, encouraging students to consider the site’s potential as a healing landscape for displaced individuals regardless of species.

How have students integrated nature into their designs to support well-being?

EM: The studio follows a reciprocal healing theme: displaced communities contribute to ecosystems through environmental engagement, while landscapes serve as a healing agent in return.

We draw from multiple influences, including UVA Professor Emeritus Reuben Rainey’s work on healing gardens, Jenny Roe’s co-authored Restorative Cities (with Layla McCay), and Kenneth Helphand’s Defiant Gardens, which explores gardens as sites of refuge. Adrian Carr Zaretsky's co-authored Transpecies Design (with Michael Zaretsky) encourages viewing landscapes beyond human-centered perspectives, prompting students to consider connections between displaced people and migrating or endangered species.

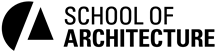

Field sketching and ecological observation are integral to the course. This term’s site visit included hikes to sketch potential building sites, woodland paths, and shorelines. I also introduced a GIS-based smart phone app that my research assistants and I are adapting to track refugee movements. We tracked our site exploration in Maine, creating a geo-referenced composite record of landforms, species, and habitats.

Next Steps for Shelter Research & Teaching

What new directions do you see for this research, and how might design education evolve to address displacement?

EM: There are many potential areas for new, focused investigations. I'm currently working with other academics and practitioners to improve the ability to rapidly interpret context in shelter scenarios when capturing and analyzing displacement tracking data on forcibly displaced people, potentially abetted by AI tools as an aid to design problem-solving. Another key objective is developing more complete curricula that integrate best practices for shelter and settlement design, informed by a network of other architecture schools' studio explorations and real-world practice.

Better preparing US-trained architects for international shelter work could involve domestic service projects, particularly addressing climate-related displacement. USAID has noted US architects often lack exposure to low-resource displacement scenarios. Addressing domestic conditions could help bridge this gap, though such efforts require great care to avoid burdening or creating false hopes for displaced communities.

With the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reporting 122.6 million forcibly displaced people—nearly double since 2015—the scale of displacement and resource scarcity demands new approaches. Humanitarian design requires calculated risks, rapid data analysis, and unconventional thinking. Architects and landscape architects must prepare for urgent, high-stakes decisions under uncertainty, one of the core objectives of exploring these issues in a design studio.